You go out into avalanche terrain, nothing happens. You go out again, nothing happens. You go out again and again and again; still no avalanches. Yes, there’s nothing like success! But here’s the critical fact: from my experience, any particular avalanche slope is stable 95 percent of the time. If you know absolutely nothing about avalanches, you automatically get a nineteen-out-of-twenty-times success rate… Thus, nearly everyone mistakes luck for skill.

You go out into avalanche terrain, nothing happens. You go out again, nothing happens. You go out again and again and again; still no avalanches. Yes, there’s nothing like success! But here’s the critical fact: from my experience, any particular avalanche slope is stable 95 percent of the time. If you know absolutely nothing about avalanches, you automatically get a nineteen-out-of-twenty-times success rate… Thus, nearly everyone mistakes luck for skill.

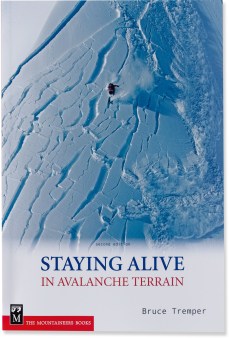

— Bruce Tremper, Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain

Backcountry skiing is never 100% safe, but good habits drastically improve our odds of staying happy, healthy, and alive out there.

Both good and bad habits spread virally among backcountry skiers via conventional media, social media, aprés ski story swapping, and because of the lasting tracks we leave behind in the snow.

We spread bad habits by leaving bad tracks or good habits by leaving good tracks. Ironically, some of the most talented riders and filmmakers set the worst examples — from a safety perspective — for the rest of us to follow.

We can learn a lot about snow conditions by studying the tracks left by other people, wind, and avalanches. Conversely, we can get ourselves into trouble by blindly following bad tracks or by failing to read the natural warning signs smeared across the snowy peaks.

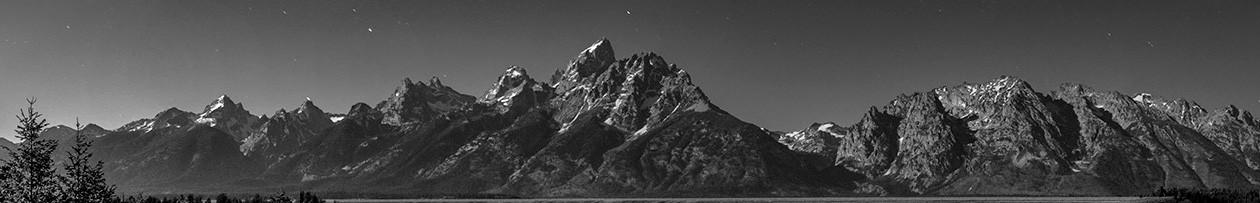

I have seen a lot of sketchy human tracks in the Tetons this winter. The following analysis of bad tracks I came across recently is dedicated to learning from the mistakes of others.

***

Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) continually gains popularity with backcountry skiers and snowboarders. More people playing in and connecting with the Tetons is a good thing, and it’s not too crowded up there… yet .

Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) continually gains popularity with backcountry skiers and snowboarders. More people playing in and connecting with the Tetons is a good thing, and it’s not too crowded up there… yet .

The minor peaks closest to parking get tracked up within a week or two of each storm, but longer approaches offer untracked skiing and sweet solitude all winter and spring.

Finding established skin tracks and boot packs up the popular peaks is a welcome relief from having to set them after storm cycles. Unfortunately, many neophyte GTNP skiers don’t know the safer and more efficient routes up the peaks or the notorious slide paths to avoid. Thus, a lot of bad tracks are spreading bad habits.

Here are some recent photos documenting this bad track trend, but first a glimpse at the snowpack during the time they were taken.

After a very snowy February the Tetons experienced warm temps and ample sun for most of early March. On March 15th BT Avalanche Center reported 8″ of snow with strong WNW winds. On the 17th they reported 14″ of fresh with strong WNW winds which prompted a CONSIDERABLE forecast and the following warning from BT Avalanche Center on March 18th:

Snowfall rates in the mountains exceeded two inches an hour yesterday afternoon. This snowfall was accompanied by westerly to northwesterly ridgetop winds that ranged from 30 to 45 miles per hour. This scenario produced wind slabs with depths up to two feet in wind loaded terrain. These slabs, which formed on slick sliding surfaces, could be easily triggered by backcountry travelers on a variety of aspects and elevations.

The following day I went for a mellow tour up Shadow Peak and saw that these warnings had not been taken to heart by all backcountry travelers.

These photos were taken from the lower summit of Shadow Peak. My partner and I wanted to keep watching this situation unfold but intense mid-afternoon sun was warming the snowpack to the point where we agreed that it was best to head down, so we did.

***

This article is not intended to belittle folks who are just getting acquainted with the Tetons or to proclaim the “right” way to play in the mountains. It is intended to get people thinking for themselves.

None of us sprung from the womb knowing how to safely travel through avalanche terrain, and none of us are immune to making mistakes or getting unlucky. Any “experienced” skier overconfident enough to poke fun at novices is begging for a piece of potentially fatal humble pie. I’ve had a few. Do you want a slice?

There is no 100% right way to backcountry ski, but there are lots of ways to do it wrong. Some skiers can spot others doing it wrong because we previously put ourselves in similarly stupid situations.

I put my skins on backwards for my first tour in GTNP and have been benighted more times than I’d care to admit. I used to be one of those sketchy skiers making sketchy tracks in sketchy spots on sketchy days. I mention my own mistakes because acknowledging mistakes is the first step in learning from them and preventing repeat offenses.

Maybe I’m writing this article for my own sake more than yours.

For education’s sake in general, let it be known that over the last decade I have had five unforgettably scary avalanche experiences in the Tetons. Maybe you can learn something from my mistakes.

Towards the end of my first Wyoming winter — back when I was invincible and knew everything — I suddenly found myself sitting on the crown of a two foot hard slab avalanche as it propagated ~200′ across the funnelling chute to my left. Below me the reason I’d stopped so abruptly — a snowboarder who was hiking uphill after getting cliffed out — stared up into the slide. I looked on in horror as it washed over him and off the cliffs below. Luckily he dropped his board and hugged a tree, perhaps saving his life and my future sanity.

On a sunny June day fifteen months later I got caught in a wet slide that carried me down 4 Shadows on Cody Peak . Like many skiers that day I’d ridden the Tram up and headed out the gates. Our first lap on Cody had been creamy corn, so we went for sloppy seconds.

On our second run I kicked off a small slide that oozed playfully at first but soon became serious. It gained momentum quickly, slammed me from behind, took me for a terrifying ride, beat me up a bit, and stole my favorite pair of sunglasses.

Luckily I lived to learn the basics from these novice mistakes, and they motivated me to study snow science and exercise more caution.

A few years later I had a similar wet-slide experience in The Narrows on the East Face of Teewinot: the whole face seemed firm and stable except between the tight walls of The Narrows where sun-bathed rocks and running water had made a pocket of shallow snowpack sloppy. As I skied down into the slot the top 6″ of slush started to move. Fortunately, I skirted out of the fall line just as it really got going, and took another lesson to heart as I watched it gain mass and velocity for ~1500′ vert before pouring off the large cliff below.

The biggest slide I’ve been a part of was also on Teewinot but mid-winter on it’s North facing lower flanks. I stopped hard on a flat spot ~15 feet back from a steep rollover to test slope stability. My stop triggered a terminal slide at the rollover with a 4-6 foot crown that propagated several hundred feet in both directions and ran full path.

Luckily I was the first person in our party: the carnage that took place below didn’t seem survivable. Getting down proved a challenge because very little snow was left on the mountainside. That winter (2009-2010) we had a persistent weak layer of depth hoar on shady aspects, and I obviously wasn’t respecting it enough.

The most eye-opening and humbling avalanche experience I’ve had took place on the Grand Teton on a sunny but cold March day. I’d been watching the South side of the Grand all winter and saw a window for taking a closer look: persistent high pressure for two weeks in which 2″ of total snowfall had been recorded at JHMR. Stabilizing sun and wind events. Certainly just going up for a looksie couldn’t hurt…

The most eye-opening and humbling avalanche experience I’ve had took place on the Grand Teton on a sunny but cold March day. I’d been watching the South side of the Grand all winter and saw a window for taking a closer look: persistent high pressure for two weeks in which 2″ of total snowfall had been recorded at JHMR. Stabilizing sun and wind events. Certainly just going up for a looksie couldn’t hurt…

My partner Dani and I made an attempt but got turned around by rapid warming at the Teepee Col. We stashed some gear there, kept a close eye on conditions, and tried again with our friend Nick a few days later.

Dani and I made the summit but Nick had to turn around before the technical section due to stomach problems. Before splitting up we discussed: none of us were too worried about Nick having avalanche issues while descending alone because the heavily sun and wind affected snow was very firm and hadn’t seen any sun yet that day.

Dani and I found firm, stable snow all the way from the valley floor to the summit and back by way of the Stettner-Chevy-Ford Route. In my opinion we had great ski mountaineering conditions except for brutal refrozen debris piles from previous days’ wet slides down low.

We were all bummed that Nick had gotten turned around by stomach bugs, so the next afternoon he and I headed back up Garnet Canyon and camped at The Meadows in hopes of making another attempt of the same route. BT Avalanche Center had reported 1″ of snow the night before at 8800′ and no new snow at higher elevations so we hoped to find similar conditions to the previous excursion.

We did not find similar conditions.

We were still pretty tired from our previous trip but the bootpack was already in, the climbing gear was still up at Teepee Col, and our weather window was forecast to close the day after tomorrow.

As Nick and I booted up from The Meadows under windless starry skies we found the faintest dusting of snow in the existing bootpack. When we reached the Teepee Snowfield we found 1/4″ of uniformly deposited fresh snow. In the sketchy slot between Teepee Col and Glencoe Col there was no new snow, just the crusty remnants of our bootpack and ski tracks.

As Nick and I booted up from The Meadows under windless starry skies we found the faintest dusting of snow in the existing bootpack. When we reached the Teepee Snowfield we found 1/4″ of uniformly deposited fresh snow. In the sketchy slot between Teepee Col and Glencoe Col there was no new snow, just the crusty remnants of our bootpack and ski tracks.

As we wrapped around the corner into the Stettner Couloir conditions changed completely. Our beloved bootpack disappeared into ankle deep snow. A few steps later the snow was boot deep, then knee deep, then waist deep, then titty deep. What little we could see higher up on the route did not look similarly snowy. Apparently the wind had deposited a great deal of the snow from the recent trace snowfall event into this thin slot called the Stettner.

We retreated back around the corner and discussed our options.

After a few minutes of discussion we decided to keep going, so we roped up, set a good anchor, and roshamboed to see who got to more thoroughly enjoy the sketchy slogfest. I lost and started swimming and burrowing my way up the steep, snow-filled couloir.

When we got to the Chevy Couloir our old bootpack reappeared and we found firm, stable snow all the way up to the summit. The wind had blown every scrap of fresh snow off the peak’s upper S faces.

As we descended we were concerned about negotiating the bottomless pow in the Stettner so we skied most of that section on double rope rappels. Below the lower ice bulge we went off rappel and enjoyed a few perfect pow turns in a steep and unusual place.

We rounded the corner, skittered carefully from Glencoe Col to the Teepee Pillar and enjoyed perfect corn all the way to the valley floor.

So what does this self-aggrandizing story have to do with avalanches?!

Two months later I was talking with a friend who happened to be skiing the West Hourglass on Nez Perce the same day that Nick and I swam up the Stettner Couloir. From across the canyon he spotted us as we were descending near the Teepee Pillar. A few seconds later he spotted a thick cascade of snow pouring off the cliff below the Stettner Couloir, the snowy slot where Nick and I had been mucking around for the last half hour.

If we’d been a few minutes later or had destabilized the snowpack a wee bit more we may have gotten flushed off that cliff to our deaths.

My friend showed me a picture of the snow waterfall, and I’ll see if he still has it. In my opinion, the awareness this article is intended to bring about is too important to wait on tracking down another scary photo. Plus, more scary photo ops are available in the Tetons almost every day.

Watch what you’re doing out there or you might get your tracks’ picture taken for an article like this (or for a mainstream story documenting the latest avalanche fatality in the Tetons).

Looking back at the avy forecast for that beautiful March day in 2010 when we narrowly averted disaster the general warning sez:

“Low hazard does not mean no hazard. At the higher elevations west-northwest winds have formed isolated pockets of surface slab up to 18 inches deep.”

The isolated pocket Nick and I encountered was over six feet deep. Two days earlier it was firm. One inch of snow had been reported.

Perhaps all veteran and aspiring Teton skiers should bear in mind that the BT Avalanche Forecast only applies from 10,500 feet down to the valley floor. The highest peak rises 3,277 feet above the forecast area: more than two additional Mt. Glory bootpacks of vert.

The high peaks generally get a lot more snow and much stronger winds than Mount Glory or JHMR are exposed to. They are steeper and more varied. They are much less predictable.

Few people even try to analyze the snow safety up there. There’s a reason that BT Avalanche Center forecasts only extend to 10,500 ft: even the best forecasters in the field can’t reliably assess the grandest Tetons.

Skiing the high peaks is always dangerous. Winter descents in soft snow are even riskier. Spring descents in soft snow may be even more dangerous than winter descents because of warmer average temps combined with more direct and intense rays from the sun.

A few years ago very few people were attempting mid-winter descents of the high peaks, and usually only after periods of sustained high pressure. Now lots of people are going after the big lines on the first sunny day after significant snow and wind events.

I’ve been lucky up there. Other people have been even luckier.

The quote this article started off with is worth repeating. The book it is from is very much worth reading and rereading. One Love. Peace.

You go out into avalanche terrain, nothing happens. You go out again, nothing happens. You go out again and again and again; still no avalanches. Yes, there’s nothing like success! But here’s the critical fact: from my experience, any particular avalanche slope is stable 95 percent of the time. If you know absolutely nothing about avalanches, you automatically get a nineteen-out-of-twenty-times success rate… Thus, nearly everyone mistakes luck for skill.

You go out into avalanche terrain, nothing happens. You go out again, nothing happens. You go out again and again and again; still no avalanches. Yes, there’s nothing like success! But here’s the critical fact: from my experience, any particular avalanche slope is stable 95 percent of the time. If you know absolutely nothing about avalanches, you automatically get a nineteen-out-of-twenty-times success rate… Thus, nearly everyone mistakes luck for skill.

— Bruce Tremper, Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain

This is bullshit. You sit in the background and criticize people for the decisions they’re making for themselves as if you have the authority. Then brag about the amount of likes you got, only cause people love to criticize the people actually going for it, from their iPhone. All of your criticisms were of people who obviously had knowledge and made decisions, right or wrong they were theirs, not yours. Go make your own decisions if your so smart. 👎✌️

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, C. I do make my own decisions. One decision I’ve made is to avoid bootpacking up sketchy faces over cliffbands when there’s a big fat couloir with a clean fall line right next to it. Another decision I’ve made is to speak my mind, just like you did in your comment. Sometimes that involves criticizing people who are setting a bad example which others inevitably follow.

Most of “the people actually going for it” with “knowledge” are smart enough to avoid the high peaks on warm sunny days shortly after heavy snow and wind events. You’ll see them out there in droves — and I might even join them — when the conditions are right for skiing the high peaks.

LikeLike

Who the fuck cares…?

LikeLike

Well, I care for one, which is why I wrote this article. The 537 people who liked this article on Facebook and the 6 people who shared it on Twitter also care. I think it’s safe the say the family and friends of backcountry skiers also care. Do you need more examples or is that sufficient?

LikeLike

I had been drinking whiskey when I read this and it got me fired up. I apologize for being a douche. Again that wind doesn’t load the sliver because there is no snow available for transport. It was just all loose, new, deep snow in the couloir. Had I had the right equipment such as Verts i would have had no problems. Lesson learned was have the right gear. Your articles are good and you’re a good writer. I enjoy reading the posts.

LikeLike

Great article, well written, entertaining, and so true

LikeLike

Great article max!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure who u are or what u know about avalanches but I am the one that put the booter up the left side of the sliver and I ill tell u now i never felt to exposed even knowing what was below me… the couloir itself was to deep to boot so we took it up the left side. We were early on this not to worried about the sun at the time of our ascent. Also thw sliver doesn’t get loaded with that wind. No snow to transport off rocks… anyway quit calling people out and go ski. We made the right decision to ski from where we were.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the input, anonymous. If you want to know who I am and what I know about avalanches you should read the whole article because that’s what the second half is about.

If the couloir itself “was too deep to boot” are you sure it wasn’t windloaded? Every ESE facing slope in the high peaks looked windloaded by the strong WNW wind so it’s hard to believe that the E facing Sliver didn’t get loaded up too.

Your descent tracks looked really good, but I think your ascent track was super sketchy. I’m glad you read part of this article. Have fun out there.

LikeLike

Good read Max. Always insightful to reexamine past experiences. Also, when you have such a blatant display of a bad decision as you did from the top of Shadow the other day, I think it’s a great idea to photograph it/start the discussion of what happened. That’s how people learn.

Anonymous, to say that the Sliver “doesn’t get loaded” is dangerously ignorant. Winds can affect gully features like the Sliver in a wide variety of ways, usually none of them contributing to stability. Like Max said, wallowing in the couloir perhaps should have tipped you off to the new load it was bearing.

-Nick

LikeLiked by 1 person